By: Charity Anderson, Ph.D., Staci Gilpin, Ph.D., Marta Pulley, MS-IDT, and Courtney Plotts, Ph.D.

January 17, 2024

A Case Study in Innovation

In our collective journey as women deeply immersed in the world of online higher education, we have steadfastly embraced the tenets of feminist pedagogy. Our approach is grounded in the ethos of collaboration and communal contribution, underpinned by a strong commitment to authenticity, inclusivity, and the acknowledgment of diverse lived experiences. This dedication to feminist principles recently culminated in a transformative experience at Courtney’s “Culture Think” conference, held in October 2023.

The conference emerged as a beacon of innovation within academic circles. It wasn’t just an event; it was a renaissance of sorts, challenging and reshaping our vision of what academic conferencing could be. Centering on cultural responsiveness and instructional design, the conference boldly stepped away from the hierarchical norms that often overshadow larger conferences. Instead, it fostered an environment where dialogues were not just encouraged but thrived.

Interestingly, our connections prior to the conference were tenuous at best. Courtney and Staci, Courtney and Marta, Staci and Charity – our interactions were limited to the peripheries of professional spaces. This detail underscores a critical critique often leveled at feminist approaches within socially driven communities and learning networks: the inherent challenge of building in-depth relationships without substantial social capital.

However, it was precisely in this environment – one marked by intimacy and safety – that we discovered an ideal setting for fostering meaningful professional interactions. The conference became a haven where those with limited connections could engage, interact, and contribute. It was a place where barriers were dismantled and new bridges were built, enabling access and fostering a sense of belonging among all participants.

As we reflect on this experience, we realize that it wasn’t just about attending another conference. It was about being part of a movement that champions a more equitable and collaborative approach to learning and professional development. It was a reaffirmation of our commitment to principles that not only guide our work but also shape our vision for a more inclusive and responsive future in higher education.

The sessions, conducted in a hotel suite, provided a blend of intellectual stimulation and comfort, complete with food, drinks, and cozy couches. This relaxed setting facilitated a transition from structured scholarly talks to more engaging, interactive formats, like Staci’s session, which evolved into a writer’s workshop and inspired this collaborative blog post. Such experiences underscored the critical roles of empathy and mindfulness in our professional lives, setting the groundwork for deep and impactful learning.

Our reflections on this unique conference, which includes dynamic engagement, collaboration, and empowerment, draw inspiration from Niya Bond’s concept of “feminist facilitation” in “The Future of Faculty Development Is Feminist.” As we present this novel conference framework, echoing the transformative educational ideologies that guide our work, we aim to guide future organizers and participants toward a more inclusive and engaging professional development model. This article delves into our reflections on these experiences, showcasing how the “Culture Think” conference served as a case study in innovation and perfectly encapsulates our envisioned structure for academic conferencing.

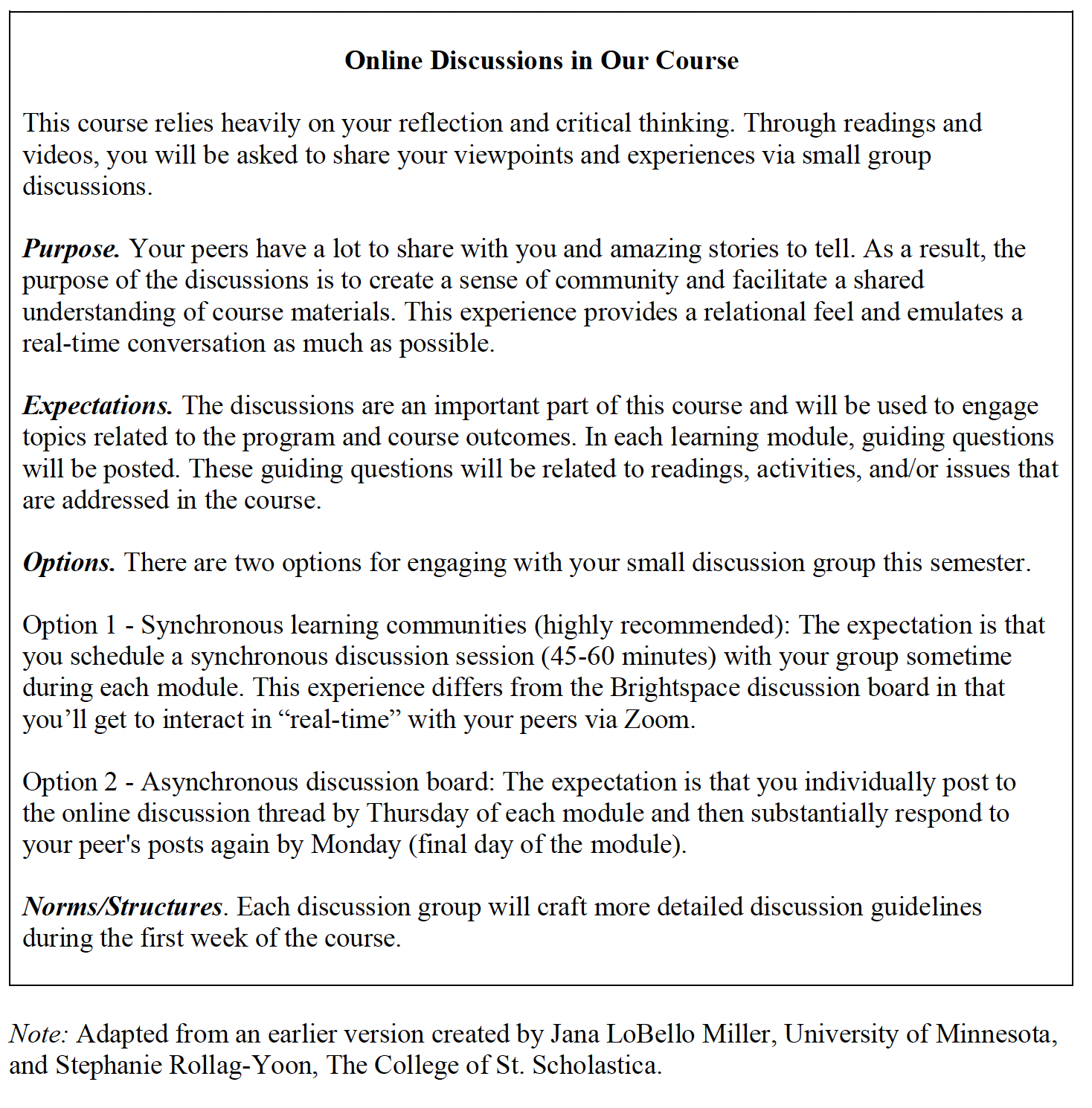

Photo: “Collaboration in Action: Participants at Staci’s session engaging in a dynamic writer’s workshop.”

Collaboration and Communal Contribution

The “Culture Think” conference format deviated from traditional academic practices by fostering a culture of collaboration over competition, deeply rooted in feminist pedagogical principles that prioritize inclusive participation (Hesse-Biber, 2011). The “Culture Think” conference format draws inspiration from feminist theorists (hooks 1994; Kamler 2001) and is in harmony with contemporary educational theories that recognize learners as co-creators (Romero-Hall 2021) and critical figures in shared leadership models (Chick & Hassel 2009). Courtney, the conference founder and organizer, made a conscious effort in her planning to reflect the feminist view of knowledge as a communal, cooperative process. The conference structure is intentionally designed to promote collective learning adaptability and meaningful connections as sessions are scheduled but also provides ample downtime and meals together or apart so that we can recharge in our own unique ways.

Participants are more than just attendees; we are integral to co-creating knowledge. This approach built lasting supportive networks and a sense of community. Charity aptly summarized the essence of the conference, stating, “I thought there was no reason not to be a part of this… it was definitely not what I did not want to be a part of—a typical conference.” This sentiment highlighted the uniqueness of our conference, which favored authentic connections over conventional formats, crucial for impactful learning experiences.

Our reimagined format also sheds light on the traditional mechanisms of academic knowledge production. Typically, a standing presenter faces a seated audience, creating a hierarchical dynamic and sometimes leading to acts of humiliation and feelings of inferiority and insecurity in academic conferences (Meriläinen et al., 2021). These traditional means and modes of doing and knowing are isolating, exclusive, and transactional, and this is a more radical and communal approach. Our conference, in contrast, champions a space for intimate relational knowing, challenging traditional conference norms and valuing vulnerability and emotional engagement, thus marking a significant shift from the typical detached, non-emotional academic discourse. This dynamic was notably apparent as attendees were encouraged to freely ask questions and offer comments in real-time, fostering unique emotional connections by sharing personal challenges and successes.

Photo: “Unity in Diversity: Charity, Marta, Staci, & Courtney at the closing dinner, immersed in shared stories and laughter.”

Promotion of Authenticity and Inclusivity

The conference format epitomizes the idea of “free spaces,” as defined by Evans and Boyte (1979), serving as a melting pot for uninhibited idea exchange and innovation beyond traditional cultural norms. The notion of “free spaces” is deeply rooted in feminist pedagogical principles that emphasize the value of diverse thoughts and experiences (Neimand et al., 2021). In these free spaces, participants are encouraged to express themselves spontaneously, fostering an environment where divergent thinking is accepted and celebrated.

This atmosphere of openness at ‘Culture Think’ was vividly captured by Courtney’s observation: “Like artists, their [attendees’] creative moments don’t happen in this very well-structured conference… It kind of happens when having lunch or sitting on the sofa.” Her words paint a picture of an academic conference transformed into a dynamic space, where exchanging ideas resembles casual yet invigorating coffee chats more than formal presentations. The informal interactions that flourished in these settings were instrumental in nurturing authentic connections and fostering innovative thoughts.

The transformative power of authenticity in academic discourse was evident throughout our four days together. Informal discussions and exchanges often happening in the peripheries of structured programs became the breeding grounds for true connection and groundbreaking ideas, showcasing the immense potential of embracing authenticity in academic environments. To illustrate, Staci shared with the group early on that she was in the early stages of planning a non-profit. From that moment forward, Courtney, Charity, and Marta, embraced her planning as if it was their own, often stopping what they were doing (e.g. whether it be enjoying a meal, a quiet walk, or facilitating a session) to share ideas that popped up with her. Needless to say, this would not have happened in a large conference venue.

Recognition of Lived Experiences

Central to the ethos of the conference format was the recognition and validation of personal narratives, a cornerstone of feminist pedagogy (Hesse-Biber, 2007). We cultivated an atmosphere where we felt safe and supported in sharing our stories, ensuring everyone could be authentic. This approach not only fostered a sense of community, belonging, and, ultimately, friendship but also enriched the overall learning experience.

Staci’s reflection on the conference atmosphere highlights this ethos: “It seemed like we were all able to be our full selves and tell our stories. It was safe to do this.” The diverse range of stories shared, from Marta’s insights into Ethiopian traditions to Staci’s anecdotes about her dog’s Instagram page, exemplified the rich, multifaceted nature of our professional dialogues. These stories went beyond mere anecdotes, weaving personal experiences into the fabric of professional learning and development.

By integrating these lived experiences into our conference framework, we acknowledge the varied human stories behind the academic professionals. This approach emphasizes that professional development is not solely about academic knowledge but also about understanding and appreciating the diverse human experiences that inform and shape our perspectives, approaches, and contributions to knowledge.

Photo: “Intimacy in Learning: Marta leading a session in a cozy, close-knit setting, facilitating heartfelt sharing.”

Charting a New Course in Academic Conferencing

In redefining the academic conference format, our ambitions extend far beyond merely introducing a new model. Our goal is to spark a movement, a fundamental shift in the way academic gatherings are perceived and conducted. We envision transforming these events into vibrant, inclusive, and empowering spaces, deeply rooted in the principles of feminist pedagogy. Our conference serves as a tangible example of this vision, demonstrating how the application of these principles can weave a rich tapestry of collaboration, authenticity, and shared experience. This echoes the insights of Eduard Lindeman’s seminal work on adult education from 1926, emphasizing that adult learning flourishes in environments where experiences and knowledge are co-created in a community setting.

Our intention is not to supplant traditional conferences but to provide an enriching alternative. This alternative, steeped in feminist pedagogy and practice, caters to those in higher education who yearn for a professional development experience that is not just informative but transformative. We imagine a future where academic conferences are dynamic experiences, brimming with the energy of shared learning and mutual growth, resonating with Lindeman’s concept of adult education as a collaborative and transformative journey.

As we continue to shape the future of academic conferences, we are mindful of the lessons and values gleaned from this pioneering experience. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that such transformative experiences may not be universally accessible. While some of our institutions provided full or partial funding for attending the conference, we must consider those who lack such financial support. Our challenge is to ensure that this innovative approach to professional development is accessible to all, regardless of their financial circumstances.

We extend an invitation to the academic community to join us in creating spaces that are not only equitable and participatory but also exhilaratingly transformative. These spaces could take various forms – from online versions of conferences like “Culture Think” to small, local gatherings in community spaces. In these environments, every voice is heard, every story is valued, and each participant becomes an integral part of our collective journey towards a more inclusive and diverse world of knowledge and learning. Lindeman’s perspective on adult education serves as a guiding light, reminding us that the journey is as significant as the destination, highlighting the process of learning and growth as much as the outcomes.

References

Chick, N. & Hassell, H. (2009). Don’t hate me because I’m virtual: Feminist pedagogy in the online classroom. Feminist Teacher: A Journal of the Practices, Theories, and Scholarship of Feminist Teaching, 19(3), 195-215. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/105946/.

Evans, S. M., & Boyte, H. C. (1992). Free spaces: The sources of democratic change in America. University of Chicago Press.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (Ed.). (2011). Handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis. SAGE publications.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Kamler, B. (2001). Relocating the personal: A critical writing pedagogy. SUNY Press.

Lindeman, E. (1926). The meaning of adult education. New Republic, Incorporated.

Meriläinen, S., Salmela, T., & Valtonen, A. (2022). Vulnerable relational knowing that matters. Gender, Work & Organization, 29(1), 79-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12730

Neimand, A., Asorey, N., Christiano, A., & Wallace, Z. (2021). Why Intersectional Stories Are Key to Helping the Communities We Serve. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://doi.org/10.48558/4KQ2-9Z32

Romero-Hall, E. (2021). How to embrace feminist pedagogies in your courses. Association for Educational Communication & Technology. https://interactions.aect.org/how-to-embrace-feminist-pedagogies-in-your-courses/